Can Connected Health Data Help Close the Gap in U.S. Maternal Mortality Rates?

At the Future of Health Data Summit this Fall, economics professor and author Emily Oster began her fireside chat with Rep. Lauren Underwood (IL-14) using staggering statistics.

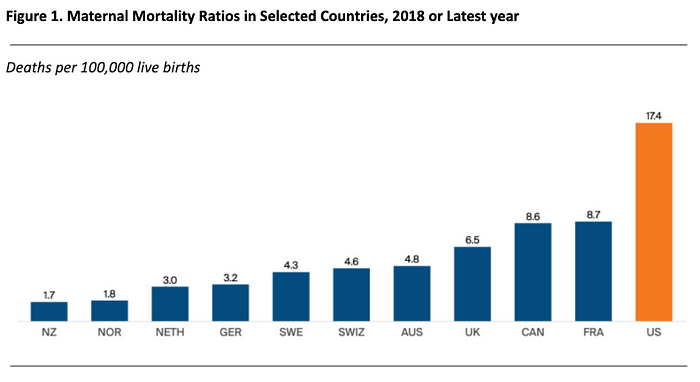

- In the U.S., 17.4 maternal deaths occur per 100,000 pregnancies.

- This translates into 660 mothers dying each year during pregnancy, birth or shortly thereafter.

- The maternal mortality ratio for Black women (37.1 per 100,000 pregnancies) is 2.5 times the ratio for White women (14.7) and three times the ratio for Hispanic women (11.8).

These maternal mortality numbers are alarming for the U.S., a nation with the highest GDP that spends more than any other country on healthcare (see Figure 1 showing US maternal mortality rates compared to other countries). Professor Oster and Representative Underwood laid out the plight of maternal death in stark numbers and human impact. Together, they championed the healthcare needs of all women, especially women of color and their babies while shedding light on the complex data landscape that must be woven together to pinpoint the risks for maternal mortality.

The Data Gaps in Maternal Health

The barriers to improving maternal health start with gaps in data. Maternal death is not an event isolated to the birth event in the hospital. It is an event whose risk factors emerge upstream early in the pregnancy, through the birth and for a period afterwards. Medicaid, a state run program, pays for two-thirds of births to Black mothers. As a state-run program, these patients will not be found in many commercial payer data sets.

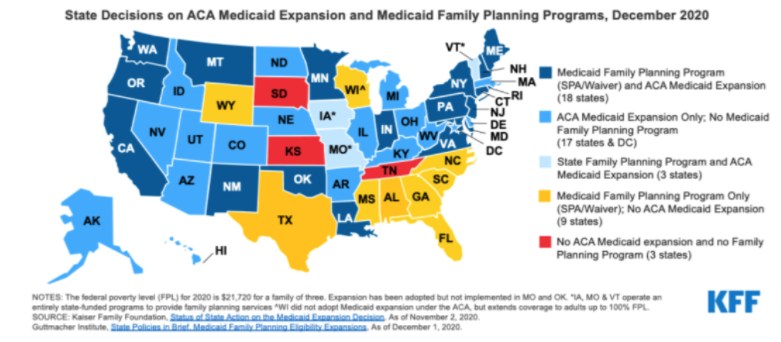

Even if those patients’ data could be collected from state Medicaid programs, some states like Kansas, South Dakota, and Tennessee did not expand Medicaid coverage beyond 60 days of the birth, and both the mother and baby lose health care coverage for postnatal care. (See Figure 2 below highlighting the status of Medicaid or state-funded family planning programs.)

Figure 2. State Decisions on Medicaid Expansion and Family Planning Programs Affect Women’s Access to Postpartum Care

Another data gap is the lack of rich social determinants of health data that includes race, housing, transportation, education, nutrition, income, and environment. Studying the extent to which each of these factors affects different cohorts of mothers is the foundation for evidence-based changes to the current care model. Importantly, data driven analysis of these factors is important to avoid stereotyping. For example, Representative Underwood underscored that even world-class athletes like Serena Williams and Alyson Felix experienced traumatic births, defying the notion that athletic, privileged Black women were exempt from the risk of death during childbirth.

In healthcare, data is useful when it is timely and refreshed continuously, however, maternal health data suffers from incredible lag. For example, the state of Illinois released their 2021 maternal mortality report using data from 2016 and 2017. The lag in maternal health data renders it nearly useless for making timely decisions in healthcare delivery, especially during a pandemic. There is also a lag in data related to substance use disorders and overdoses, which have high impact on the health outcomes of mothers and babies.

In response to this challenge, Representative Underwood and Congresswoman Alma Adams (NC-12) started the Black Maternal Health Caucus (the “BMHC”) in 2019. The BMHC has grown to over 100 bipartisan members with a goal of “elevating the Black maternal health crisis within Congress and advancing policy solutions to improve maternal health outcomes and end disparities.” The Caucus has begun to engage various participants in the healthcare community. As a result, some insurance companies have expressed interest in sharing data to support this effort.

Other Pieces to Solving the Maternal Mortality Puzzle: Paid Leave and Provider Diversity

Representative Underwood characterized other types of support needed to maintain maternal health before, during, and after their pregnancies. They include paid leave, and proper prenatal and postnatal care to support healthy behaviors and manage potential health risks. Mothers who do not have paid maternity leave are impacted the most. Professor Oster posited that paid maternity leave is one of many missing puzzle pieces that make up all the gaps in supporting the health of pregnant women and their babies.

The Family and Medical Leave Act (“FMLA”) is a labor law providing unpaid leave and ensuring job protection, but many women cannot afford to take unpaid medical leave. Representative Underwood discussed a new legislative proposal that could give workers paid family leave for 12 weeks. Her comprehensive policies include diversification of the perinatal workforce with nurse midwives, physician assistants, obstetricians, doulas and lactation consultants. These additional types of providers improve access to care, better manage health risks, and enable patients to exercise choice in their prenatal care and birth process.

The Momnibus: Legislation to Advance Maternal Health

Representative Underwood introduced the Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act of 2021 (a portmanteau of moms and omnibus). It is the most comprehensive legislation of its kind for maternal and child health. It attempts to close many maternal health gaps with mandates to:

- Make critical investments in social determinants of health that influence maternal health outcomes, like housing, transportation, and nutrition.

- Provide funding to community-based organizations that are working to improve maternal health outcomes and promote equity.

- Comprehensively study the unique maternal health risks facing pregnant and postpartum veterans and support VA maternity care coordination programs.

- Grow and diversify the perinatal workforce to ensure that every mom in America receives culturally congruent maternity care and support.

- Improve data collection processes and quality measures to better understand the causes of the maternal health crisis in the United States and inform solutions to address it.

- Support moms with maternal mental health conditions and substance use disorders.

- Improve maternal health care and support for incarcerated moms.

- Invest in digital tools like telehealth to improve maternal health outcomes in underserved areas.

- Promote innovative payment models to incentivize high-quality maternity care and non-clinical perinatal support.

- Invest in federal programs to address the unique risks for and effects of COVID-19 during and after pregnancy and to advance respectful maternity care in future public health emergencies.

- Invest in community-based initiatives to reduce levels of and exposure to climate change-related risks for moms and babies.

- Promote maternal vaccinations to protect the health and safety of moms and babies.

With this legislation, Representative Underwood sought to address some of the biggest underlying risk factors for maternal mortality. In her home state of Illinois, the number one cause of maternal death is mental illness. Title VI of the Momnibus will help build the infrastructure to support recent mothers who need community-based treatment. Title V, supports data collection to review causal analyses of maternal mortality so that the true cause of death can be fully evaluated.

Maternal mortality varies greatly by state but today, states do not have a mechanism to share data so they can cross compare risk factors, care approaches, and outcomes. As the discussion drew to a close, Representative Underwood offered an open invitation to the healthcare technology community to engage the BMHC in identifying a solution to the fragmentation of maternal health data. She offered a hopeful concluding statement: “One of the things I know about technology companies is that if you have a culture of openness, a culture of solving problems and a culture that says let’s do something, you can do it.”

Edited by Elenee Argentinis, Head of Marketing, Datavant

Resources

- Black Maternal Health Caucus. (2021). Black Maternal Health Momnibus. Retrieved from https://blackmaternalhealthcaucus-underwood.house.gov/Momnibus

- Ranji U., Gomez, I., & Salganifcoff A. (2021 March 9). Expanding Postpartum Medicaid Coverage. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/expanding-postpartum-medicaid-coverage/

- Tikkanen, R., Gunja, M.Z., FitzGerald M., & Zephyrin L. (2020 November 18). Maternal Mortality and Maternity Care in the United States Compared to 10 Other Developed Countries. Retrieved from Commonwealth Fund https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/nov/maternal-mortality-maternity-care-us-compared-10-countries

Editor’s note: This post has been updated on December 2022 for accuracy and comprehensiveness.